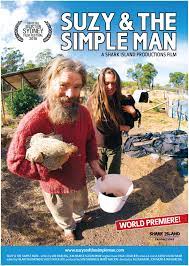

Suzy and the Simple man, 2016. Australian documentary film.

Why do some people get an Australia medal and celebrate themselves unashamedly, and others, in an unasssumed manner pass notice or attention with ease simply going about their lives?

When an academic assumes they can deny sentience and state “You’re nothing but a waitress…[or]Better than being a waitress” I asked, “What did they think of themselves around others to assume that superior stance or their subjectivity mattered more than an other’s?” Suzy and the Simple Man, an Australian 2016 documentary revealed to me that some people receive medals for being adventurers as well as living without a WAG or woman-handbag to attend Galas and balls as a star. Suzy was beautiful in her own way and through her love and admiration for her garden, her health and her partner Jon Muir. Throughout the documentary I never really knew who the “simple man” was. He simply existed as simple as possible. I thought I was watching two people struggling through illness and taking in the day, slowly and with generosity as part of their environment and community. At the end of the documentary, I realised that Jon Muir had an Order of Australian Medal for being an adventurer, a mountain climber and a trail blazer or path finder for the few who dare, like Mt Everest. Instead of constantly imposing a fascist stance directed towards others they both lived in love simply.

Would they assert dominance over others, stating “You’re nothing but a waitress!”? Like the academic, I can’t assume and answer my question. I can only suggest that my sentience and my well-being as someone who is not a waitress but belittled for being a mother who cares about her children as someone aware of the perverse attachments some people make when they are determined to destroy a life or many lives. Some people abuse their social positions and desire to be flattered in public: to gain a medal is to gain admiration. The documentary revealed that Jon Muir simply kept exploring and living as the man he always was regardless of a medal of honour. The documentary didn’t focus on this part of his life – a day or an hour that potentially made him dress up differently for an occasion (if he attended) and instead followed him enjoying the sunshine, sunset, his partner’s company, his business and his prize winning community vegetable show. Like the Good Life characters going against Penelope Keith, the couple smiled and enjoyed what others would find too difficult and unable to find any comfort without running piped water and spa baths: a simple life. A life living off the grid and I assume a life away from the torment and torture others would impose: get a hair cult, a real job, and live in the grid paying taxes. They built their business and they built their home: simply and from what they loved and knew. Family traditions had taught Suzy how to garden well. I admired her involvement in the local school educating students about gardening. She made her interests look worthwhile and with integrity, before cancer set in, involved young people in something she knew a lot about: gardening and well-being evolved from it.

As for people knowing about whether a waitress or mother feels when they determine they don’t is another story still kept hidden. The story that some have claimed medals and accolades unfairly and unjustly for work they have never done. I have known some who belittle others because they were a school captain, studied law, or came top in the state in English and never again revealed this was worth it. The titles became their worth and others their path they trod on rather than stepped aside, acknowledged or allowed to grow and develop beyond their weed-like parasitic nature. Australia Day medals have never fascinated me and neither have adventurers. The story changed this as I looked up the people and discovered they had contributed a lot to society and culture that I knew little about. Other people found what they had achieved worthy. I found their story that advocated simplicity and less judgemental values and denial of emotional connections worth something more than a medal.

Clearly, I remained the same after watching the documentary: an Australia Day medal is meaningless. They flatter those who know the people and just like most considered socially below most wealthy people celebrated in life are the overworked, poorer, overlooked people, a medal recipient never really demonstrates gratitude to the society that holds the medal with value. Of course, I ask what is generosity and gratitude in the light of this documentary?

I find that an academic reducing a person to “nothing but….” ungrateful and without generosity and knowledge that people don’t need a medal nor social status sign or symbol. It is, like in other conversations, disgusting to hear social status playing out in society so easily and accepted without question. “I am an academic…I am higher up than you…” as childish, immature and without sentience nor humanity. Blinded by status and the need for social flattery stands in contradiction to the film’s purpose: eyes wide open Suzy makes her own decisions about cancer treatment that we all need to consider when faced with the difficult struggles whether to seek medical treatment or alternative medicine wasn’t her advice.

She lived revealing her path and we didn’t need to copy or mimic because that might prove dangerous. We could persevere just as she did with our own choices supported by loved ones. She reveals a vulnerable woman uncertain of her future as well as a woman determined to follow her own path and make decisions that suited her.

The academic again pushes and says “You have no proof…you can’t prove it…” Of course, these are ghosts and the voices that suggest reduction and determination to beat and defeat or control and compete are from past conversations involving many people – hurt and attempting to reframe this hurt with others who have experienced similar belittlement and denial of their differences. Aggressive people – men and women – don’t allow questioning to explore. Jon Muir must have been a strong person to explore and to adventure away from social moorings. Suzy did the same. She wasn’t simply the partner of Jon Muir OAM. She was a sentient being who lived generously and simply off the grid. The grid. A place for competition and denial, for some, in the gaps – those who lived without wealth and still struggled do so dangerously. Shamed for being poor, the wealthy (cashed-up citizen) gain access to admiration and dignity they don’t deserve and haven’t earned. The nameless masses who build up the empire toil unnoticed and without medals or accolades. A community gifts people and takes away. The wealthier (or more cashed up) live off this system, the grid or the organised flattened plane where like Descartes they stop up their ears and close their eyes determined to consider their own existence worthy before – their reflection?

Well, just like a woman ridicules another and puts her supposedly in her place, the reflection she projects is one of the man she attempts to gain admiration from. In her place, her embodied stance she abuses and controls other women unquestioned and re-presents her own presentation of masculinity as the only project for society. Suzy presented me, the spectator, with a question, another woman creating her spirit and her life loving and supporting as genuinely and generously as she felt she could. Without contemporary confines – hair and make up come to mind easily – she questions the grid and what it means to be a strong woman living off the grid.

© Cate Andrews, 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.