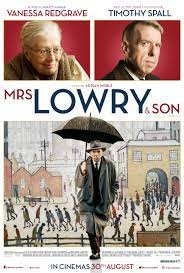

Mrs Lowry and Son, 2019, director Adrian Noble.

I knew nothing about L.S Lowry prior to watching this film. I still don’t claim to be an expert, like some I watched with. They knew all – from the film and other articles – they made their claim. This knowledge was theirs: they knew. I sat silently listening to them. I was silenced by the film, not by their knowledge. I felt strange. L.S. Lowry was painted in a light that was grey and sensitive. His mother, insensitive to his existence, abused and neglected him. He remained loyal, looking after her – is this care? I wandered off from the chatter, and thought about care. What if I was bedridden, who would take care of me and how would it be done? The cruelty that was and became the life L.S Lowry on film was difficult. Feminist theory has argued that women need re-education and care to change and develop away from the financial dependence that patriarchy had imposed. Some feminists suggest that men need the education and the impossibility, like Shirley Valentine suggests, marriage is “like peace in the Middle East: There is no solution”. The mother-son relation was seen, through my eyes, a pleasure for the mother to feel touched when her hair was brushed and flattered into a childish stupor when a neighbour paid her attention. This girlish performance of admiration and adoration was short lived.

Mrs Lowry complained of her middle class upbringing and the shame of living “working class” (and on borrowed, creditors money for these complaints!) She belittled and demoralised her deceased husband and son. She ranted that she never wanted a son or child. SHe abused him for his need to paint what he saw: factories, stooped workers dressed in grey and their stories. She abused him for this obscenity to her sensibility: sailing boats, once admired by the neighbour, became the focal point. Dirty factories and ugly portraits were as shameful as his poor position in the workforce. Mrs Lowry didn’t – in the film – connect with her son and his diversity: art was not a hobby. Art was who he was and how he experienced his world. His mother wanted him to see a doctor for this appeal and self-expression. I didn’t claim to know like those around me “knew”. I felt the director and writer offered me a path to feel empathy for an artist and their struggles within their family and with society. For this knowledge, the gift of connecting with someone, was important. I couldn’t know L.S. Lowry or claim this. I did feel angry that someone was treated this way because of wealth and class. I did connect with his feelings of invalidation: the cruel anxiety that the mother threw away from herself at him through harsh, critical words to set herself in a place above him and of authority was something I have researched in education, the arts, and through psychology research.

Mrs Lowry reminded me of a lecture about generalised anxiety: how this impacts on the way people believe they are being viewed by others and their reality. Often distorted, generalised anxiety locks people up – metaphorically – in their homes and away from gatherings because of anxiety. They don’t enjoy public speaking and they find relief through avoidance. Mrs Lowry locked her son up in her own class anxiety. Instead of going outside and simply enjoying a day – beyond class distinctions there’s always the sunshine or feeling of rain or interacting with a milkman or butcher. Mrs Lowry chose to demoralise all of these. What did she fear the most? Looking like a poorer woman or not having the civil awareness to interact with people as humans? I saw her as a cruel, fear filled woman ageing in her bed and delighting only in the touch of her son. Her loneliness was cruel. Her class upbringing made her this cold, and lonely.

Posthumously, L.S Lowry was offered a Knighthood and he turned it down. Unlike most who enjoy the fame and spotlight, the film offered us some insight: his mother was no longer living so he didn’t need to accept the gesture. He painted what he saw: the outside world is what I have briefly noticed in his artwork. Factories, red doors and stooped people dressed in blacks and greys. Head down, walking, moving, not leisurely resting. Leisure time was not present in his paintings. Or was the walk something more for this class of workers? Did some, like him, have another life we can’t know beyond the soot, the debt and their stoop?

© Cate Andrews, 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.