“We write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospect.”

― Anais Nin

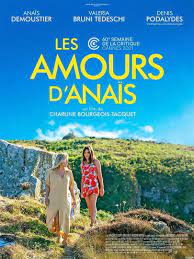

Disgust. A conversation about the character Anaïs in Anaïs in Love, French 2021 film directed by Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet.

Why talk about disgust? Conflicting meanings and reasons why disgust is powerful and socially bonding and considered moral whereas I have reframed it, from embodied feelings to consider it as a feeling that is unethical.

Disgust means to me someone who has behaved in a way that disgusts me. They have done something that denies conversation as well as defies my own questioning regarding their self-entitlement to behave in a certain way in a social setting. Their defiance doesn’t present me with creative energy nor an opening to question my own bias nor subjectivity. The behaviour is a barrier and invalidates future acts that might change society or provide happiness and relief from the ordinary. This “barrier” feeling, meaning no potential, depth nor possibility for transformation (either the act the person has done nor my thinking to attempt to reframe) is like stopping a stream needing constant motion to cleanse, renew and explore. Invalidation is one concept I have considered to discuss the inner feelings of disgust.

The barrier is a blocking, a wall that behaviour “behaves” (I think I’m trying to reach the moment of feeling like stating a world that worlds, or a lack that lacks) to control me and my own needs. And the behaviour invalidates my safety and expectations in a community. Some people simply live in a way that’s disgusting and their treatment of others (their well being, need for safety, enjoyment, and social cohesion or intelligence with empathy or awareness of alterity and diverse interests).

Disgust isn’t moral for me it’s ethical and for me it pushes me and my inner being. Disgust, feeling that disgust is another psychosocial attempt to control. I feel controlled by the barriers that feeling arouses. It’s an attachment that’s perverse or against my own nature. This is unethical for me.

Disgust becomes a feeling of oppression and the oppressiveness of the other that determines me and wishes only to subjugate, control and dominate. Their perspective is the only one. The wish to dement; or to repeat their behaviour to produce and reproduce their social, what disgusts me, as the only access to the social. The oppressive feelings is that unethical, felt disgust. It’s not moral, for me, because I have repositioned myself through questioning as the one the disgusting or act of behaving in a certain way can’t stand and determines to overpower and defy their own discomfort and feelings (immaturity, for example as well alienation and isolation from their group) to cast aside any connection to rule or control.

One film that reveals an example of this (I have experienced this in many situations) is 2021 French film Anaïs in Love directed by Charline Bourgeois-Tacquet. I couldn’t stand the immaturity of the young main character Anaïs. Her selfish, self-centred pursuit of whatever she wanted and with disregard to others’ feelings was, I assume, a perspective of French freedom and sexual liberation. I usually attempt to consider other perspectives offered to me through film narratives, and almost accepted her older female (played by Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi) lovers’ approach that she needed to express herself. Her allure was her energy and free nature. But when Anaïs didn’t get her own way I didn’t find this freedom. I simply thought her immaturity was disgusting and unethical. She was selfish. The film, like the title explored female sexual expression and attraction. I did consider the erotic stories of the author with the same name Anaïs Nin and this quote from her writing:

“Love never dies a natural death. It dies because we don’t know how to replenish its source. It dies of blindness and errors and betrayals. It dies of illness and wounds; it dies of weariness, of witherings, of tarnishings”.

My feeling of disgust revealed more about my own sense of identity and love as well as my values: that Anaïs in the film didn’t know how to replenish, she simply took. Her character, I felt, lacked social development and love that would end up alone simply because sexual attraction would wither with her need to feel free without connections. A strange feeling. The questions that might be better explored through French philosophy about freedom and whether Sartre’s often quoted assertion “Man is condemned to be free” might suggest that Anaïs’ freedom for me was a condemnation that was unethical or disgusting because it was individual and selfish because of her lack of acceptance. Her need to impress herself and feel wanted oppressed others’ needs.

For me, the character drained the sources of others’ generosity or sexual attraction to her and love never really matured nor developed as a way to understand and connect with people. Disgust, beyond abject physical repulsion or rejection, becomes part of the discussion about maturity and community not simply a power of horror oppressing diversity or differences that is generally accepted as a moral attitude towards control and social meanings of disgust.

© Cate Andrews, 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.